The aurora borealis takes many forms, and every single display is different. Time of night, solar wind speed, magnetic field strength, moonlight, and many other factors influence how it looks. The northern lights also appear different depending on who is watching. The more stargazing experience someone has, and the younger their eyes are, the more details they will see. It’s also important to remember that cameras will always see more colors than the human eye does. Cameras can take long exposures, while our brains cannot.

If you chase auroras long enough, these are some of the different types you might expect to see.

Curtains

In the Arctic, auroral curtains are very common. Stripes of green, purple, or red swirl across the sky. These shapes change rapidly and can quickly morph into other types of aurora.

Arc

Auroral arcs are not the most exciting type of aurora. That’s because they are constrained to the northern horizon and don’t show very much movement. But when you see an arc start to brighten, that usually means that a substorm is imminent.

Pillars

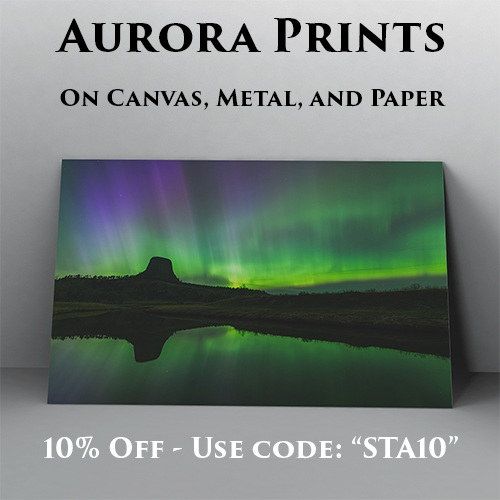

In mid-latitudes, aurora pillars are most common. During a substorm, they can quickly rise up from the north and drift across the horizon. Usually they are green at the base and topped with red or purple. Though the actual aurora may be far to the north, pillars can be seen from quite a distance because they are hundreds of miles high.

Rays

Rays are similar to pillars, but more commonly seen in the Arctic. Because rays may appear directly above you, the perspective is different. Rays can quickly morph into other types of aurora.

Corona

Coronas are the most spectacular form of aurora. It appears directly overhead. Rays, pillars, and pulses rise up from every horizon like a flame, converging at the zenith. The show is mesmerizing to watch. Coronas are commonly seen in the Arctic. But they are much rarer in lower latitudes, requiring a very intense geomagnetic storm.

STEVE

STEVE (Strong Thermal Emission Velocity Enhancement) is a rare atmospheric phenomena only recently classified in 2016. Technically it is not an aurora, but always appears alongside it. STEVE takes the form of a narrow arc extending hundreds or thousands of kilometers aligned east to west. STEVE is spotted more frequently in mid-latitudes and is often preceded by a green “picket fence”.

Deep Sky

A deep sky, or photographic aurora can be easily missed. It’s not visible to the eye, but only picked up by a long exposure on a camera. It happens more often than you would expect when geomagnetic activity is weak.

Stable Auroral Red (SAR) Arc

Stable auroral red arcs are another rare type of aurora that may be related to STEVE. But it is much fainter and harder to spot with the naked eye. On November 5, 2023, a strong geomagnetic storm spawned an SAR arc that was photographed as far south as Texas.

Pulsing

Pulsing aurora often occurs after a substorm, as activity is winding down. Patches of auroral light pulse on and off. This is more easily seen in a time lapse than in a still image.

Blue

Blue auroras may be seen with pillars that reach very high into the atmosphere. They are so high up that they are illuminated by sunlight. Therefore they can only be seen within a few hours of sunset or sunrise.

Nitrogen Fringe

In the Arctic, some of the more active aurora swirls may have a red or pink “nitrogen fringe” at the base. These can be very bright, and change rapidly.